For Borrowers, Banks are Bust – But Private Credit is Just Getting Started

By JB Capital

The end of ZIRP-era “stocks go up” shook loose many market assumptions, not the least of which was the 60/40 portfolio paradigm as stocks and bonds increasingly correlated. But, like 2008’s Great Recession, public confidence in commercial banking institutions became one of the first casualties of a higher interest rate regime.

A slew of bank failures shook consumer and depositor confidence. Still, the same shortcomings created a wake-up call for investors – investing in legacy banking, whether through bonds backed by loans or equity investments in the bank itself, is no longer the “safe alternative” to growth stocks in a rocky economy. Likewise, stricter lending requirements made capital acquisition an increasingly difficult proposition for all but the largest and most profitable firms (who often have little need for large loans in the first place).

But we saw private credit slowly coming to the fore in 2022, and today, its ability to marry quality borrowers with hungry investors is all but unmatched by traditional banking institutions.

When Banks go Bad

Though our national news cycle is measured in hours rather than weeks or months, you likely remember 2023’s Silicon Valley Bank run and subsequent collapse. The saga reflects banking’s overall poor state today – especially in an era where rates will remain “higher for longer,” putting pressure on even the most rigidly stress-tested institutions.

To recap, here’s what went down:

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), situated in the heart of America’s tech startup sector, found itself flush with cash as low rates and unicorn-hunting investors threw as much capital as they could at founders who, in turn, deposited the money with SVB. Accepting deposits from the public is one of two core commercial banking sector competencies.

Commercial banking’s second core competency is putting those deposits to use through lending, whether business, personal, auto, mortgage – whatever. As you can imagine, their primary moneymaking comes from business lending. But SVB faced a unique set of circumstances – they did minimal lending. Why?

- In many cases, founders had access to as much venture capital as they wanted, although it came at the cost of equity.

- Even if startups wanted to borrow rather than issue equity, SVB’s risk control mostly prevented them from doing so. Business loans are usually asset-backed or require historical free cash flow to secure the loan. Those startups tended to be unprofitable, with limited tangible assets to borrow against.

A look at SVB’s final quarterly filing shows that the bank’s loan-to-deposit (LTD) ratio sat around 0.40. By comparison, national bank LTD ratios trend close to .80 on average, depending on the bank’s size. The LTD is a liquidity metric that usually helps analysts determine whether a bank is overextending itself; in this case, it shows that SVB was critically lacking viable loan opportunities.

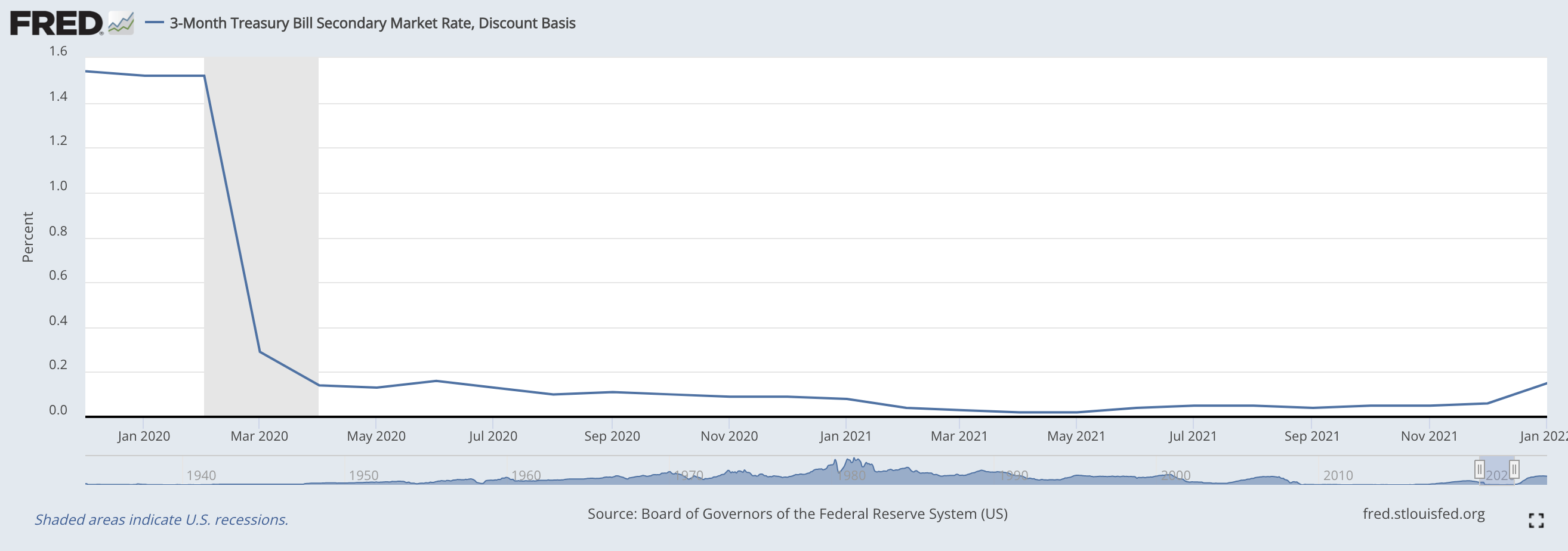

Of course, SVB couldn’t just let depositor cash pile up – they have to deploy capital somewhere, lest shareholders get antsy and depositors ask why their interest-bearing accounts aren’t yielding. In this case, the obvious answer is to invest in quality fixed-income assets like Treasury Bills and highly rated corporate paper. One problem – in 2020 and 2021, bottom-barrel interest rates meant the juice wasn’t worth the squeeze. In fact, between April 2020 and January 2022, 3-Month Treasurys didn’t break the 0.2% barrier.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data

So, SVB did what made the most sense to them then. Assuming the ZIRP-era free-for-all wouldn’t end, management invested its loose change into longer-term Treasury Notes that, while still paltry, yielded a bit more than their short-term counterparts.

The rest is history: rates went up, SVB’s paper losses mounted as bond values fell, liquidity requirements demanded the bank realize some losses, and depositors dashed to get their cash out of SVB’s hands. The subsequent bank runs caused SVB’s collapse, and depositors are still fighting to claw back their uninsured balances as many maintained accounts well exceeding FDIC maximum limits.

The Takeaway

So what? It’s easy to argue that SVB’s collapse is a niche case that, while unfortunate, doesn’t apply widely to the banking sector. Furthermore, you can likely make a case that its collapse will help prevent incidents of the same type as executives and regulators have a case study to base future decisions against.

Unfortunately, consistent corporate mismanagement and regulatory misalignment all ensure the same problems will continue unabated until the next banking crisis.

To recap:

Borrowers Couldn’t Borrow

Potential borrowers couldn’t secure funds from SVB’s lending programs due to ineligibility. A lack of assets and profitability tied SVB’s hands in this case. But pull back the lens to middle-market companies, small corporations, real estate developers, and the ineligible for large commercial loans, for whatever reason, and there’s a whole class of potential borrowers underserved (if served at all) by legacy banking. Likewise, those companies tend to shy away from private equity as the terms are too restrictive (board seats, executive shuffles) or equity demands too high.

Investors Lost their Shirts

In this case, we can lump “investors” into two broad categories when looking at the banking sector: depositors seeking yield from an interest-bearing account and shareholders invested in the bank itself that expect a return (typically from net interest income generated by lending, which ties back into our prior problem).

Today, though higher rates are pushing interest-bearing deposit account yields higher, you’re not going to beat short-term investable fixed-income assets like Treasurys that you can simply buy yourself. At the same time, shareholders lost their principal investment and projected cash flow from dividend distributions, leaving them in worse shape than the depositor class.

What if there was an alternative that better served both borrowers and investors, leaving legacy banking behind?

It’s called private credit.

What is private credit?

In many ways, private credit sounds too good to be true. It’s a dual-use alternative asset, benefiting investors seeking yield and borrowers hungry for capital, that:

- Lends much-needed capital to borrowers ineligible for commercial loans without demanding equity stakes.

- It tends to yield well beyond standard short-term Treasurys, lending itself to income investors.

- With proper due diligence, it has little risk of principal loss, which, combined with yield, skews the risk/reward profile higher than the highest-yielding savings account or junk bond.

You’ll generally see private credit lenders and investment funds leverage one of four “types,” though some circumstances call for a blended approach:

- Direct lending: The most popular, common, and straightforward to understand, direct lending involves companies and real estate developers borrowing directly from a private lender or pooled capital group. Direct lending is essentially the same as a commercial loan in that interest is paid throughout the loan’s duration, and the lender holds the loan until maturity rather than selling it to secondary servicers.

- Mezzanine financing: Mezzanine financing is somewhat comparable to convertible bonds in that it lets lenders convert their position to equity holdings if the company defaults or otherwise can’t repay the debt. Critically, in the case of default, other lenders are repaid before mezzanine financiers. Because of that risk, mezzanine financing also tends to carry higher interest rates for the borrower.

- Distressed debt: Distressed debt, as the name implies, involves lending to companies with no other alternative besides bankruptcy or liquidation. The lender usually has a stake in helping the company pivot back to viability or prepare to profit from liquidation proceedings and asset sales.

- Venture debt: The other side of venture capital, venture debt is similar to direct lending but targets unprofitable companies to help fuel their growth and (eventual) profitability.

WHY is Private Credit Better for borrowers and investors?

The primary benefit to borrowers is that they can access much-needed capital when commercial lending is unavailable or offers terms unsuitable to executive decision-makers. Higher interest rates accelerated private lending interest on account of two primary conditions:

- Banks tend to scrutinize borrowers more heavily in a higher interest rate regime, creating untenable terms or outright denying more borrowers. Private lending covers the gap between commercial lending denial and having to fork over equity.

- As commercial loans come due, many companies refinance their existing loans through private credit lenders to kick the can down the road until interest rates fall (payment in kind).

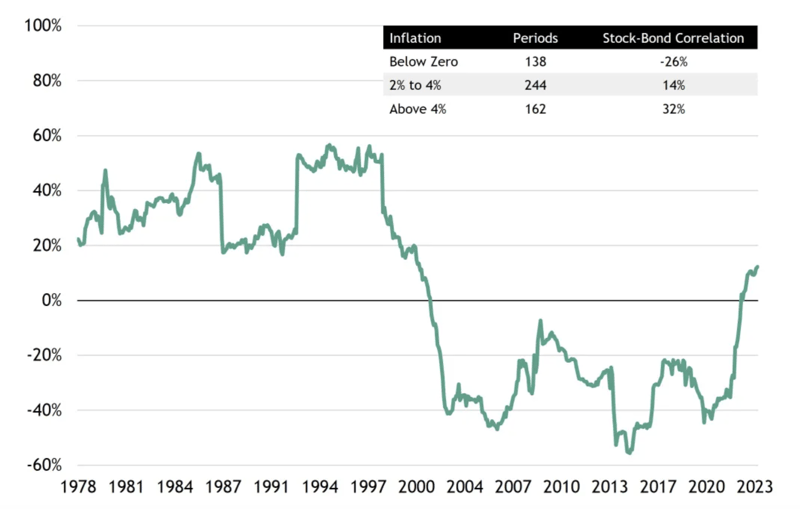

The era of uncorrelated stocks and bond movement is all but over, forcing many investors into fixed-income alternatives to satisfy risk tolerance requirements or otherwise diversify their portfolios.

Source: Blackstone

But, at the same time, higher interest rates create conditions like we saw with SVB – if rates stay “higher for longer,” or the Fed hikes rates further, bond values fall and can wreak havoc on a leveraged portfolio.

In these cases, private credit is a fixed-income alternative and often yields well above the already-high Treasury rates. In fact, today, direct lending yields an average of 10.6% - well above standard fixed-income instruments. Better yet, many private credit agreements include floating rate terms, meaning the interest payments increase alongside the Federal Reserve’s target rate. This helps maintain the profitability gap between standard fixed-income investments and their private counterparts.

Private Credit's Place in Tomorrow's World

Clearly, private credit is a preferable alternative to commercial banking for borrowers and investors alike. And the secret is out – research firm Preqin reports that 90% of polled LPs think the massive $1.5 trillion private credit market exceeded their expectations over the past year. Likewise, 45% plan to increase their private credit allocation as part of their alternative investment stack this year, and more than 50% plan to do so sometime thereafter.

If you haven’t yet dipped your toes into private credit, now is the time – a handful of stocks are increasingly propping up the stock market, and continued recessionary risk all but assures higher rates for longer, putting continued pressure on legacy banking. Leave the old regime behind while there’s still time.